MYCENAE AND CADMEA

The Heroic Age ended abruptly, as we already noted, in the twelfth century B.C. Ancient scholars calculated this on the basis of the genealogies of ancient clans, and modern scholars arrive at a similar date, though they use different data and methods to make their calculations. Both ancient and modern scholars agree also that the cause of the fall of that age was not a natural cataclysm, but an invasion of tribes which in the twelfth century moved from the north of Greece all the way to the extreme south of the Peloponnesus, from where they even reached the island of Crete; and all along the way they destroyed all centers of civilization. These were Doric tribes. In Greek mythology, as we already mentioned, the invasion is known as the Return of the Heraclids, since Doric rulers claimed descent from Heracles. (This is why the king of Doric Spartans had the ashes of Alcmene, mother of Heracles, moved to his country).

But here the question which we had asked already returns: Greeks believed firmly that a great Heroic Age once took place; but what basis do we have to claim that it was the twelfth century which saw its destruction?

We owe an answer to this question to just one man: Heinrich Schliemann. In love with ancient Greek myths, especially those which had been immortalized by Homer, he devoted his life to proving that they weren’t a fantasy, but a reflection of actual facts. Beginning in 1870, over the course of thirty years, Schliemann conducted great excavations in places famed by great myths. He showed that in all those places there had once existed great palaces, full of treasures and objects of art, populated by rich and powerful men; the lifestyle of those times was totally different from that of the classical Greeks; and it all came abruptly to an end in the twelfth century.

The largest and most impressive palace of those times was in Mycenae. It is located in Peloponnesus, in a country known as Argolis. The rulers of Mycenae, the myths tell us, ruled over many surrounding countries; this is why we now call the Heroic Age "the Mycenaean Period". But besides Mycenae, many other centers flourished at the time; many are mentioned later in this book, but for now three must be named: Tiryns, in Argolis, clearly visible from Mycenae; then Pylos, on the Western coast of Peloponnesus; and Knossos, on Crete. True, magnificent palaces had been built in Knossos in earlier times, also, but it remained an important center in the Mycenaean period as well. Schliemann’s excavations – and those of his successors, since work has continued down to present time – allow us to propose the following rule: every locality in Greece which plays a role in mythology also preserves remains of a flourishing cultural center from the Mycenaean period.

The arriving Dorians destroyed Mycenaeans. All castles fell – even though the walls of many had been built of rocks so large that the succeeding generations refused to believe that they had been built by the hand of man; stories were told that they were built by Cyclops instead. The Mycenaean states collapsed. All major tombs were plundered by the raiders. All life in Greece returned to primitive, barbarian norms. No one built large palaces or castles anymore. The tradition of mural painting was broken off. The art of making fine gold, silver and bronze jewelry was lost. Several centuries of darkness had to pass before there arose the first stirrings of a new high culture, which in time we have come to call The Classical.

But the Dorians have not destroyed everything. Some remains of the Mycenaean glory have survived, both on the surface and underground; and the simple folk who’d lived in the simple huts at the feet of the grand castles, too, has survived. It is these people who have preserved from generation to generation the memory of the notable events of the ruling Mycenaean houses, which had fought each other for land, power and women. And the songs which had once been sung in the halls of the kings also proved more durable than stone or bronze; passed from mouth to mouth, they traveled down the centuries. Heroes grew to match gods, and fragments of Mycenaean history, wrapped in myth and poetry, became immortal, like pre-historical petrified plants.

In Thebes also the memory of the past remained alive – both thanks to legends and the castle’s remains. Walking towards the house of Simmias, the plotters passed the foot of the Cadmean hill. At that time there stood upon Cadmea many large new buildings, but people still pointed out fragments of some ancient walls and associated them with stories of the great events of the Heroic Age. Nowadays, it’s the other way around. Thebes is only a small town and its houses are packed closely on the entire top of the Cadmean hill. It’s difficult to excavate here: one would have to knock down half the town in order to get to the layers beneath. Only from time to time, when some digging work must be done, can one excavate a bit of the ancient ruins which run deep below the present street level.

Despite these difficulties, the Greek archeologist Antonios Keramopoulos, by digging whenever an opportunity presented itself, managed to excavate many-thousand-year old remains in the center of the city. Gradually, between 1906 and 1921 he uncovered a network of rooms, corridors and courtyards which had once been part of a large palace complex. The biggest of these rooms may have been a kind of throne room, while others, smaller, may have served as the apartments of the court ladies, as many small feminine decorations found throughout seem to suggest. There even remained small fragments of wall painting; it had portrayed women in long dresses advancing in a ceremonial procession, perhaps to offer a sacrifice to a deity. Similar paintings – in content and technique – had been found in the ruins of Mycenae and Tiryns. This alone suggests that the palace on Cadmea dates to the same period and that it is therefore Mycenaean. It’s also clear that the palace had been destroyed by a violent fire: there is a very thick layer of ashes on the palace floors.

At first, it was difficult to determine how large an area the complex had occupied. Keramoupulos himself suspected that all other traces of the palace had been wiped out from other sections of the hill by the subsequent construction, but, in 1937, another Greek archeologist, Spiridon Marinatos, determined on the basis of a series of small findings that the Mycenaean palace had once occupied the whole hilltop and even descended down its slope in a series of terraces. It was, in other words, in its time an impressive complex, one of the largest in the Greece of Heroic Age. Who built it? Who ruled here? Was the terrible fire the work of the same Dorians who destroyed other Mycenaean palaces of the time?

In connection with the last question, some doubts quickly arose. Certain evidence seemed to suggest that the fire predated the destruction of the Mycenaean world by some two hundred years. It seems to follow that, unless the great fire was an accident, then Cadmea was destroyed in one of the wars between Mycenaean princes. Did the ancient myths preserve tales of a war against Thebes? Yes: the myths tell the stories of two famous expeditions of seven princes against Thebes; of these, the second culminated in a capture of Cadmea. But we also find in the myths a story that the palace on Cadmea was once destroyed by the lightning of Zeus. In any case, both archeological data and the ancient myths told us that a great catastrophe touched Thebes at the peak of the Mycenaean age.

In 1921, the last year of his excavations, Keramopulos found, in one of the corridors, great amphorae, which had once been used to preserve oil and wine. Pottery is the most common object found in archeological excavations, but these amphorae became a cause of great excitement: over twenty of them featured inscriptions in some kind of a script. It was a strange script, quite unlike anything ever seen in later Greece, and no one was able to decipher it. But it was soon recalled that as early as 1900 the English archeologist Evans had found on Crete, in the palace of Knossos, hundreds of clay tablets covered with short inscriptions; their letters looked just like the letters now found in Thebes!

Since remains of this script had been found in two distant centers of the same civilization, the suspicion arose that the script was shared by all Mycenaeans; and since it was the Heroic Age, if we could only decipher the script would we not be able to learn the truth about the world in which the great myths had been born? Not everyone agreed. Some claimed that the script was really only known on Crete and that the Mycenaeans of the mainland did not know it at all; and the amphorae prove nothing because they had been brought to Thebes from Crete.

Was it possible to reject this claim? Yes, by quoting the story of the tablet from Alcmene’s tomb. The grave certainly dated to Mycenaean times and the bronze tablet was covered with a script which no one in Classical Greece could read; its letters appeared similar to Egyptian, which is why it was then dispatched for decipherment to Memphis. Now, looking at the clay tablets from Knossos, and the inscriptions on the amphorae of Thebes, it was easy to see how an unpracticed eye could mistake some of the letters for Egyptian hieroglyphs; after all some of the signs are really no more than drawings of objects: it is easy to make out heads of horses, pots of various shapes, an ear of wheat, the silhouette of a man, another of a woman, the horns of a goat, an arrow, a sword, a spear, a tripod, a chariot, a wheel – and many others. Of course, even their similarity to their Egyptian counterparts is only superficial; and most letters from Knossos and Thebes are either lines or combinations of lines; there are about eighty of them, and it is thanks to them that the script is called, somewhat prosaically, “linear B”. (The name “linear B” comes from the fact that on Crete there had once existed a similar script, older and more primitive; it is called “linear A”).

At any rate, it is easy to understand and forgive the Spartans, who, at a loss, turned for help to Egypt. But for us the tablet from Alcmene’s tomb is proof – an indirect proof, of course – that linear B was used during the Mycenaean period not only on Crete, but also on the mainland. Haliartus, where the supposed tomb of Alcmene had been located, was in the Mycenaean period a rich settlement, just like several other localities on the plane surrounding Lake Copais. It is not surprising that the memory of the tomb survived so many centuries following the fall of the Mycenaean world. In the whole of Greece ancient Mycenaean cults survived and many Mycenaean tombs were thought to be the burial places of famous heroes.

Several score years have passed since 1921, when Keramopulos discovered in Cadmea the famous amphorae with mysterious inscriptions. Today no one doubts that Mycenaeans had their own script because many fragments of it have since been discovered on the Greek mainland. What is more, we can now read linear B. The heroes have spoken. Are the texts of these ancient inscriptions in any way similar to what the Egyptian priest Chonouphis read in the tablet from Alcmene’s tomb?

30.12.09

28.12.09

Seven Against Thebes (8)

ATLANTIS

Simmias claimed to have gone to Egypt with Plato. Was this true, or did Simmias only say so in order to add bronze to his studies by claiming to have shared them with a very famous man? There are scholars who claim that Plato in fact never went to Egypt, even though the ancients took this for a fact. But it is certain that Plato was under a great impression of the great antiquity and durability of the Egyptian civilization; he often and openly expressed this humble admiration for it. But he did not believe that the most ancient civilization, the mother of them all, had its origin on the banks of the Nile. His views in this matter were far more interesting. He believed that great civilizations had arisen in other lands also, but that they then collapsed and disappeared without a trace as a result of natural disasters. Then, in their place, new civilizations arose, but without any connection to, or even awareness of what had gone before. According to him the greatness of the Egyptian civilization lay in its durability: in the fact that she has outlasted the rises and falls of all the others, herself remaining unchanged and untouched, like a rock in the middle of stormy sea.

Plato expressed this view, as was his habit, not directly, but through a dialogue which, he claimed, the Athenian Solon had had in the sixth century B.C. with a certain Egyptian priest. During his travels, Solon arrived at an Egyptian city in the Nile delta; it was called Sais and it was the site of worship of the goddess Neith. Local priests claimed that this goddess was known to the Greeks under the name of Athena; both were virgin goddesses, warlike, and represented with weapons in their hands: Athena had a helmet, a shield, and a spear while Neith held a spear and arrows. It’s pointless to argue whether these similarities were accidental: all that matters is that Athens had for centuries maintained close commercial relations with Sais; and for this reason alone, if none other, local priests gladly received Athenian guests and claimed common religious affiliation.

Solon took great interest in the antiquities of Egypt. He held many conversations with the priests, asking them about the origins of mankind; and he narrated to them ancient Greek myths. In the course of telling one, he mentioned that there had once been a great flood and that only two people survived it: Deucalion and Pyrrha; that all men alive today descend from those two; and that counting back the generations one could estimate when that great natural disaster took place. But these stories only elicited patronizing smiles from the Egyptian priests and someone said:

“Oh, Solon, Solon! You Greeks are such kids! There are no old men among you!”

Surprised, the Athenian asked:

“How must I understand your words?”

“You all have young souls because your souls do not contain any ancient views, grown out of a prehistorical tradition; nor do they contain any true knowledge hoary with great age. And why is this? Destruction has descended upon mankind many times before, and in many different ways. The greatest catastrophes came of water and fire, but there were thousands of other causes, too, less permanent in nature. Do you not tell the story of Phaeton, son of Helios, how he once drove his father’s chariot, but, unable to hold it in its proper path, set the whole earth on fire and was himself killed by Zeus’s lighting? So is the story told, as a myth, but the myth contains a kernel of truth, for only a small change in the trajectories of heavenly bodies is needed for fire to singe the surface of the earth; and such small changes of trajectories do happen, though eons apart. At such times, the residents of mountains and plateaus are more at risk than those who sit by the rivers and the sea. And for us, the Nile is then our salvation, as it is in other cases, too. But when gods purify the earth by flooding it with sea waters, then mountain shepherds have a chance to survive, while people in your coastal cities are carried off by rising rivers into the sea. In our own land, divine water never descends from heaven, but rises gradually and calmly from below; and this gives us time to protect ourselves. This is why in our land ancient institutions are preserved and all sorts of things of greatest antiquity.

“And thus whatever happens – with you, or with us, or with some other land known to us – whatever happens that is beautiful, or important, or lofty on some other account – all of that is recorded and preserved in our temples. As for your history, barely has one had the time to write it down when suddenly a flood descends from heavens, or some other natural disaster, like an ever-recurring disease – and what does it leave behind? Yes, at all times some small group of men survives, but these are invariably the least educated ones, unable to read. And so, your civilization is forever reborn; and you are like youth; you know nothing about the past of others, or even your own, because, well, you do not have it. All those myths of yours, Solon, and all your genealogies, well, they aren’t really much different from children’s fairy-tales.”

Then the priest began to tell Solon that that great flood, from which only Deucalion and Pyrrha escaped, was only the latest one and that before it waters have often flooded the earth. He then said that some ten thousand years ago the great goddess Athena-Neith created a great state with an ideal constitution and located it precisely where Solon called his home; only a thousand years later was the Egyptian state conceived by the will of the same goddess and based on the same political principles. That ancient Athenian state bravely resisted a great power which then, thousands of years ago, advanced upon Europe and Asia from the West, from the Atlantic. For there existed at that time, in the Atlantic, a great island, populated by a numerous and rich people. The ancient Athenians have pushed back their attacks and saved the peoples of the Mediterranean from Atlantid slavery. Later, a great natural disaster came, earthquakes and flooding. In the course of just one day and one night, the sea swallowed up Atlantis and the great armies of ancient Athenians disappeared in the bowels of the earth. A new epoch began and the memory of what happened had only survived in Egypt.

That story, which Solon was supposed to have heard from an Egyptian priest, served Plato as an introduction to a treatise on the creation of the universe; it was entitled Timaeus. Later, Plato returned to the subject once more, in his treatise Critias, in which he presented his ideas regarding the constitution of the ideal state using the examples of Atlantis and Athens before the flood.

All of this was of course only a poetic setting for a learned treatise. Yet, the myth of Atlantis, was not entirely free invention: it sprang up on the basis of certain facts. Greek sailors returning from the West reported with amazement the riches of the Atlantic provinces. Certain details of the story of Atlantis allow us to guess that news of the city of Tartessos, in southern Spain, had reached Greece; the city flourished between the years 1100 and 500 B.C. and then died out, perhaps due to a natural disaster; or perhaps some political catastrophe. Already Plato’s predecessors had magnified the story of Tartessos and had pushed it back in time.

Much has been written on this matter, much more perhaps than it deserves. But there is something in Plato’s myth of Atlantis which does deserve our attention: it reveals a very specific notion of human history, perhaps common to all Greeks of the time. We moderns tend to see history as a kind of straight line which constantly rises, every higher and steeper – despite temporary set backs – from the period of animal primitivism to ever fuller human command over the universe. But according to Plato, history should be seen as an oscillating wave, now rising, now falling in accordance with a certain ancient rhythm of changes in the universe: there have once been periods of greater civilization; times of downfall will certainly come; and then, in their wake, there will be new rebirths.

What kind of experiences could have given rise to this kind of view of history? To understand it, we must remember that one of the basic elements of all Greek education was ancient mythology, which recounted the story of the great Heroic Age. We already spoke about this: the present could not rise to the glory of that time: the people of that age had been more courageous, buildings, judging by their ruins, had been more impressive, and gods interacted with men nearly like equals. But that world collapsed, leaving no written record but only myths passed by word of mouth. Whole generations had lived in the wake of the fall like utter barbarians. The question naturally arose: perhaps before the Heroic Age there had once been another glorious period which had been ended by natural disasters of its own, whose only echoes are stories of floods and fires?

Simmias claimed to have gone to Egypt with Plato. Was this true, or did Simmias only say so in order to add bronze to his studies by claiming to have shared them with a very famous man? There are scholars who claim that Plato in fact never went to Egypt, even though the ancients took this for a fact. But it is certain that Plato was under a great impression of the great antiquity and durability of the Egyptian civilization; he often and openly expressed this humble admiration for it. But he did not believe that the most ancient civilization, the mother of them all, had its origin on the banks of the Nile. His views in this matter were far more interesting. He believed that great civilizations had arisen in other lands also, but that they then collapsed and disappeared without a trace as a result of natural disasters. Then, in their place, new civilizations arose, but without any connection to, or even awareness of what had gone before. According to him the greatness of the Egyptian civilization lay in its durability: in the fact that she has outlasted the rises and falls of all the others, herself remaining unchanged and untouched, like a rock in the middle of stormy sea.

Plato expressed this view, as was his habit, not directly, but through a dialogue which, he claimed, the Athenian Solon had had in the sixth century B.C. with a certain Egyptian priest. During his travels, Solon arrived at an Egyptian city in the Nile delta; it was called Sais and it was the site of worship of the goddess Neith. Local priests claimed that this goddess was known to the Greeks under the name of Athena; both were virgin goddesses, warlike, and represented with weapons in their hands: Athena had a helmet, a shield, and a spear while Neith held a spear and arrows. It’s pointless to argue whether these similarities were accidental: all that matters is that Athens had for centuries maintained close commercial relations with Sais; and for this reason alone, if none other, local priests gladly received Athenian guests and claimed common religious affiliation.

Solon took great interest in the antiquities of Egypt. He held many conversations with the priests, asking them about the origins of mankind; and he narrated to them ancient Greek myths. In the course of telling one, he mentioned that there had once been a great flood and that only two people survived it: Deucalion and Pyrrha; that all men alive today descend from those two; and that counting back the generations one could estimate when that great natural disaster took place. But these stories only elicited patronizing smiles from the Egyptian priests and someone said:

“Oh, Solon, Solon! You Greeks are such kids! There are no old men among you!”

Surprised, the Athenian asked:

“How must I understand your words?”

“You all have young souls because your souls do not contain any ancient views, grown out of a prehistorical tradition; nor do they contain any true knowledge hoary with great age. And why is this? Destruction has descended upon mankind many times before, and in many different ways. The greatest catastrophes came of water and fire, but there were thousands of other causes, too, less permanent in nature. Do you not tell the story of Phaeton, son of Helios, how he once drove his father’s chariot, but, unable to hold it in its proper path, set the whole earth on fire and was himself killed by Zeus’s lighting? So is the story told, as a myth, but the myth contains a kernel of truth, for only a small change in the trajectories of heavenly bodies is needed for fire to singe the surface of the earth; and such small changes of trajectories do happen, though eons apart. At such times, the residents of mountains and plateaus are more at risk than those who sit by the rivers and the sea. And for us, the Nile is then our salvation, as it is in other cases, too. But when gods purify the earth by flooding it with sea waters, then mountain shepherds have a chance to survive, while people in your coastal cities are carried off by rising rivers into the sea. In our own land, divine water never descends from heaven, but rises gradually and calmly from below; and this gives us time to protect ourselves. This is why in our land ancient institutions are preserved and all sorts of things of greatest antiquity.

“And thus whatever happens – with you, or with us, or with some other land known to us – whatever happens that is beautiful, or important, or lofty on some other account – all of that is recorded and preserved in our temples. As for your history, barely has one had the time to write it down when suddenly a flood descends from heavens, or some other natural disaster, like an ever-recurring disease – and what does it leave behind? Yes, at all times some small group of men survives, but these are invariably the least educated ones, unable to read. And so, your civilization is forever reborn; and you are like youth; you know nothing about the past of others, or even your own, because, well, you do not have it. All those myths of yours, Solon, and all your genealogies, well, they aren’t really much different from children’s fairy-tales.”

Then the priest began to tell Solon that that great flood, from which only Deucalion and Pyrrha escaped, was only the latest one and that before it waters have often flooded the earth. He then said that some ten thousand years ago the great goddess Athena-Neith created a great state with an ideal constitution and located it precisely where Solon called his home; only a thousand years later was the Egyptian state conceived by the will of the same goddess and based on the same political principles. That ancient Athenian state bravely resisted a great power which then, thousands of years ago, advanced upon Europe and Asia from the West, from the Atlantic. For there existed at that time, in the Atlantic, a great island, populated by a numerous and rich people. The ancient Athenians have pushed back their attacks and saved the peoples of the Mediterranean from Atlantid slavery. Later, a great natural disaster came, earthquakes and flooding. In the course of just one day and one night, the sea swallowed up Atlantis and the great armies of ancient Athenians disappeared in the bowels of the earth. A new epoch began and the memory of what happened had only survived in Egypt.

That story, which Solon was supposed to have heard from an Egyptian priest, served Plato as an introduction to a treatise on the creation of the universe; it was entitled Timaeus. Later, Plato returned to the subject once more, in his treatise Critias, in which he presented his ideas regarding the constitution of the ideal state using the examples of Atlantis and Athens before the flood.

All of this was of course only a poetic setting for a learned treatise. Yet, the myth of Atlantis, was not entirely free invention: it sprang up on the basis of certain facts. Greek sailors returning from the West reported with amazement the riches of the Atlantic provinces. Certain details of the story of Atlantis allow us to guess that news of the city of Tartessos, in southern Spain, had reached Greece; the city flourished between the years 1100 and 500 B.C. and then died out, perhaps due to a natural disaster; or perhaps some political catastrophe. Already Plato’s predecessors had magnified the story of Tartessos and had pushed it back in time.

Much has been written on this matter, much more perhaps than it deserves. But there is something in Plato’s myth of Atlantis which does deserve our attention: it reveals a very specific notion of human history, perhaps common to all Greeks of the time. We moderns tend to see history as a kind of straight line which constantly rises, every higher and steeper – despite temporary set backs – from the period of animal primitivism to ever fuller human command over the universe. But according to Plato, history should be seen as an oscillating wave, now rising, now falling in accordance with a certain ancient rhythm of changes in the universe: there have once been periods of greater civilization; times of downfall will certainly come; and then, in their wake, there will be new rebirths.

What kind of experiences could have given rise to this kind of view of history? To understand it, we must remember that one of the basic elements of all Greek education was ancient mythology, which recounted the story of the great Heroic Age. We already spoke about this: the present could not rise to the glory of that time: the people of that age had been more courageous, buildings, judging by their ruins, had been more impressive, and gods interacted with men nearly like equals. But that world collapsed, leaving no written record but only myths passed by word of mouth. Whole generations had lived in the wake of the fall like utter barbarians. The question naturally arose: perhaps before the Heroic Age there had once been another glorious period which had been ended by natural disasters of its own, whose only echoes are stories of floods and fires?

27.12.09

Kangxi, again

.

Kangxi's literary output isn't Nobel Prize material, but let us give the man a break: even the Nobel Prize material is often not Nobel Prize material. Unlike much Nobel Prize material, though, Kangxi's writing is, at least, always worth reading.

Spence's Emperor of China: Self Portrait of Kang-hsi is as close to an autobiography of any Chinese emperor as we will ever get. Culled from his various edicts, rescripts, and letters, all of which Kangxi wrote personally, and in which he famously, and unusually for a Chinese ruler, maintained a very personal note, the various fragments have been assembled here into chapters with titles like Traveling, Ruling, and Aging, and Sons.

Out of the book there emerges a very likable figure: a sensible and practical man, unceremonious, and forthright; one taking great pleasure (and, with age, pride) in physical activity -- during the Galdan campaign in Outer Mongolia he writes "I travel strenuously 30 or 40 li each day, eat no more than once a day, sometimes once every two, and the cold is very bitter, but I have never been happier in my life" -- and in simple food -- in Ningxia, he writes, the noodles are delicious, better than any ever served at court, and cheap, too; wise, unprejudiced, and fair. The Manchu's are braver than the Chinese, he writes, and often unruly, but they can make good scholars; the Fujianese, he writes, are turbulent and love acts of daring, but surely one cannot say that they are all worthless. To rule men, one must be neither too soft, or they will get cheeky, nor too hard, or they will be paralyzed with fear; it is OK to demote and exile men for a trifle, but death penalty should be dealt most carefully because it is irreversible; when evaluating men, look into their eyes: often a cloud in the pupil can give you a warning; and it is good policy to try to look for the good in them and to discount the bad.

The San-fan war, or Rebellion of The Three Feudatories, came close to overthrowing Kangxi's rule. I have caused it, he says in one of his edicts, no one but me bears the blame. In my decision to demote the three generals and to move them to Manchuria, I have failed to foresee that they may resist, and I have failed to listen to my ministers' advice. If I did, the whole disaster would never have happened.

At one point there is a lengthy description of his personal ministrations at the death bed of his grandmother, the Empress Dowager. For forty days he slept on the floor, by her bedside, preparing her medications, keeping her favorite foods at the ready. It may sound like a typical account of a Chinese confucian extolling his own filial piety, except that he mentions his grandmother in passing on many occasions: orphaned in his childhood, emperor at eight, Kangxi was raised by his grandmother. At fifty-seven, dreams of her will still seem significant and prophetic to him.

Unlike most men of his time, Kangxi is not superstitious; when governors report to him the appearance of the magical zhi fungus on a mountaintop under a purple cloud, a sure proof of the Emperor's virtue and promise of long life, he replies that history books are full of all kinds of magical omens, but such omens are of no use at ruling the country, and the only good omens are good harvests and contented people. Cut it out, he says in so many words.

All his life he was a student of the Tao, reading, mediating on, and discussing the Tao Te Ching (Dao De Jing) with his tutors. But his remarks on Taoist sages are acerbic; they are all either fools or charlatans (like the Archpriest Chonouphis who said he translated the tablet from Alcemene's grave), he says, none has attained immortality, how could anyone ever believe such a thing?

But at one point, perhaps the most tragic point of his life, he came near to believing in magic. His beloved son, Yinreng (Yinjeng) -- every parent, he writes, has sons whom he loves deeply and sons whom he loves not deeply -- his fourth son, whom, unlike all the others, he educated personally, grooming him for succession from the first, had to be deposed. There were various accusations against him: that he bought children for sexual pleasure, that he compromised palace security by admitting all sorts of undesirables, that he had people -- some of them ranking officials -- beaten, that he spoke wildly of his father's death and plotted his father's overthrow, etc., but the real cause for his removal was not legal, but practical: Yinreng proved emotionally unstable, wild, unpredictable and dangerous; his wives feared him and his servants fled from him; no one of his personal retinue would lament his fall, writes Kangxi. We read the subtext: as an emperor, Yinreng would not last a year. He could not be trusted with the job.

After Yinreng was deposed, a charge of magic was brought against another imperial prince, the first son, that he had employed a Mongolian witch-doctor to cast a spell on Yinreng. An investigation discovered a malignant fetish buried under Yinreng's threshold; on the day on which it was dug up, Yinreng suffered an epileptic attack, but recovered soon after and began to give the impression of having suddenly improved. Then Kangxi fell sick and Yinreng ministered by his side the way Kangxi had once ministered by his grandmother. Then the Empress Dowager came to Kangxi in his dream and she was strangely aloof, refusing to speak to him, as if she were upset with something he had done. To me, this is the moment of supreme tragedy in the emperor's life, a moment of such pain as drives men into witlessness: out of love for his beloved son, Kangxi was prepared to believe in magic and dreams. He reinstated Yinreng to Heir Apparency.

But that did not last. Soon Yinreng began to show signs of mental instability again -- mental disease often manifests itself in cycles, creating false hopes of recovery; an accusation of a coup d'etat plot was brought against the prince. Yinreng was again deposed and placed under house arrest. Until his dying day Kangxi refused to name another Heir Apparent; perhaps out of fear that he may have to depose that one, too; but perhaps because he had loved Yinreng too much. "Every parent has sons whom he loves deeply", he writes; "too deeply" we are inclined to read between the lines.

Kangxi died in 1722, after 60 years' reign. In his valedictory edict he wrote the following words, words which exemplify the simple, personal tone of all of his writings:

On the Ordos, where there were many hares

Hunting on the Ordos, the Hares were many

Open country, flat sand,

Sky beyond the river.

Over a thousand hares daily

Trapped in the hunters' ring.

Checking the borders,

I'm going to stretch my limbs;

And keep on shooting the curved bow,

Now with my left hand, now with my right.

Kangxi's literary output isn't Nobel Prize material, but let us give the man a break: even the Nobel Prize material is often not Nobel Prize material. Unlike much Nobel Prize material, though, Kangxi's writing is, at least, always worth reading.

Spence's Emperor of China: Self Portrait of Kang-hsi is as close to an autobiography of any Chinese emperor as we will ever get. Culled from his various edicts, rescripts, and letters, all of which Kangxi wrote personally, and in which he famously, and unusually for a Chinese ruler, maintained a very personal note, the various fragments have been assembled here into chapters with titles like Traveling, Ruling, and Aging, and Sons.

Out of the book there emerges a very likable figure: a sensible and practical man, unceremonious, and forthright; one taking great pleasure (and, with age, pride) in physical activity -- during the Galdan campaign in Outer Mongolia he writes "I travel strenuously 30 or 40 li each day, eat no more than once a day, sometimes once every two, and the cold is very bitter, but I have never been happier in my life" -- and in simple food -- in Ningxia, he writes, the noodles are delicious, better than any ever served at court, and cheap, too; wise, unprejudiced, and fair. The Manchu's are braver than the Chinese, he writes, and often unruly, but they can make good scholars; the Fujianese, he writes, are turbulent and love acts of daring, but surely one cannot say that they are all worthless. To rule men, one must be neither too soft, or they will get cheeky, nor too hard, or they will be paralyzed with fear; it is OK to demote and exile men for a trifle, but death penalty should be dealt most carefully because it is irreversible; when evaluating men, look into their eyes: often a cloud in the pupil can give you a warning; and it is good policy to try to look for the good in them and to discount the bad.

The San-fan war, or Rebellion of The Three Feudatories, came close to overthrowing Kangxi's rule. I have caused it, he says in one of his edicts, no one but me bears the blame. In my decision to demote the three generals and to move them to Manchuria, I have failed to foresee that they may resist, and I have failed to listen to my ministers' advice. If I did, the whole disaster would never have happened.

At one point there is a lengthy description of his personal ministrations at the death bed of his grandmother, the Empress Dowager. For forty days he slept on the floor, by her bedside, preparing her medications, keeping her favorite foods at the ready. It may sound like a typical account of a Chinese confucian extolling his own filial piety, except that he mentions his grandmother in passing on many occasions: orphaned in his childhood, emperor at eight, Kangxi was raised by his grandmother. At fifty-seven, dreams of her will still seem significant and prophetic to him.

Unlike most men of his time, Kangxi is not superstitious; when governors report to him the appearance of the magical zhi fungus on a mountaintop under a purple cloud, a sure proof of the Emperor's virtue and promise of long life, he replies that history books are full of all kinds of magical omens, but such omens are of no use at ruling the country, and the only good omens are good harvests and contented people. Cut it out, he says in so many words.

All his life he was a student of the Tao, reading, mediating on, and discussing the Tao Te Ching (Dao De Jing) with his tutors. But his remarks on Taoist sages are acerbic; they are all either fools or charlatans (like the Archpriest Chonouphis who said he translated the tablet from Alcemene's grave), he says, none has attained immortality, how could anyone ever believe such a thing?

But at one point, perhaps the most tragic point of his life, he came near to believing in magic. His beloved son, Yinreng (Yinjeng) -- every parent, he writes, has sons whom he loves deeply and sons whom he loves not deeply -- his fourth son, whom, unlike all the others, he educated personally, grooming him for succession from the first, had to be deposed. There were various accusations against him: that he bought children for sexual pleasure, that he compromised palace security by admitting all sorts of undesirables, that he had people -- some of them ranking officials -- beaten, that he spoke wildly of his father's death and plotted his father's overthrow, etc., but the real cause for his removal was not legal, but practical: Yinreng proved emotionally unstable, wild, unpredictable and dangerous; his wives feared him and his servants fled from him; no one of his personal retinue would lament his fall, writes Kangxi. We read the subtext: as an emperor, Yinreng would not last a year. He could not be trusted with the job.

After Yinreng was deposed, a charge of magic was brought against another imperial prince, the first son, that he had employed a Mongolian witch-doctor to cast a spell on Yinreng. An investigation discovered a malignant fetish buried under Yinreng's threshold; on the day on which it was dug up, Yinreng suffered an epileptic attack, but recovered soon after and began to give the impression of having suddenly improved. Then Kangxi fell sick and Yinreng ministered by his side the way Kangxi had once ministered by his grandmother. Then the Empress Dowager came to Kangxi in his dream and she was strangely aloof, refusing to speak to him, as if she were upset with something he had done. To me, this is the moment of supreme tragedy in the emperor's life, a moment of such pain as drives men into witlessness: out of love for his beloved son, Kangxi was prepared to believe in magic and dreams. He reinstated Yinreng to Heir Apparency.

But that did not last. Soon Yinreng began to show signs of mental instability again -- mental disease often manifests itself in cycles, creating false hopes of recovery; an accusation of a coup d'etat plot was brought against the prince. Yinreng was again deposed and placed under house arrest. Until his dying day Kangxi refused to name another Heir Apparent; perhaps out of fear that he may have to depose that one, too; but perhaps because he had loved Yinreng too much. "Every parent has sons whom he loves deeply", he writes; "too deeply" we are inclined to read between the lines.

Kangxi died in 1722, after 60 years' reign. In his valedictory edict he wrote the following words, words which exemplify the simple, personal tone of all of his writings:

Over 4,350 years have passed since the first year of the Yellow Emperor to the present, and over 300 emperors are listed as having reigned, though the data from the Three Dynasties -- that is, for the period before the Qin burning of books are not wholly credible. In the 1,960 years from the first year of Qin Shihuang to the present there have been 211 people who have been named emperor and who have taken era names. What man am I, that among all those who have reigned long since the Qin and Han dynasties, it should be I who have reigned the longest?

26.12.09

Seven Against Thebes (7)

.

THE ARCHPRIEST CHONOUPHIS DECIPHERS THE TABLET

Theocritus and his friends chatted about Alcmene’s tomb and waited for Leontiades and his men the leave the house of Simmias the philosopher – it was that very Leontiades who three years earlier had invited the Spartan garrison. Only after he'd gone did the plotters enter the house.

Simmias the philosopher sat upon his bed, lost in somber thought. It was unnecessary to ask: everyone could guess the answer: the pleas have had no result; Amphiteos was going to be executed. At length, after a long silence, Simmias shook off his thoughts. He looked at his guests and sighed:

“By gods, what sort of people were these who’d been here just before you arrived! They are wild beasts, not men! The old saying is right: there is nothing more odd or more disgusting than an old man in power. Even if one experienced no injustice directly himself, it is enough to see the intransigence to come to hate the regime, a regime which breaks the law, feels no responsibility before anyone, and does not even try to hear out rational arguments. Of course, young men often are like this, too, but age adds to it that special ossified inflexibility.”

One could say, in defense of Leontiades, that in his eyes Amphiteos was especially guilty. He was thought to have been the ring-leader of a previous attempt to overthrow the tyrants and their Spartan allies in Cadmea. In fact, the mastermind and animator of that plot had been young Pelopidas, long active in exile in Athens and now leading the seven plotters through the wilds of the Kithairon towards Thebes. But Leontiades did not know any of this.

Meanwhile, Simmias livened up, and, like a true philosopher, set aside oppressive thoughts. He said:

“Well, we must entrust this matter to the gods. Meanwhile, my dear Caphisias, what sort of a stranger was this who’d arrived in your house today?”

Simmias was of course part of the plot, but Caphisias preferred to remain circumspect:

“Who do you mean?”

“Why, Leontiades himself has just told me about it. He’d heard reports that a stranger had been seen at the tomb of Lysis; that he and his retinue had spent the night there; and that he slept on the ground, on a bed of tamarisk and willow. There were also, apparently, traces of some sacrifice of milk, by the remains of the fire. And at dawn he was seen asking people where he might find you, Caphisias, and your brother Epaminondas.”

Caphisias grew alarmed. He had heard no such thing himself; but he had left his house especially early in order to rush to the house of Charon to inquire there how matters stood with the plot, and with the seven coming over from Athens. He began to think aloud:

“Who could it be, that stranger? Surely, a great lord to travel with retinue. Has no one asked him where he was from?”

But Pheidolaos interrupted him impatiently because he was very curious about the story of the funeral tablet and eager to learn more in the matter. He said:

“Yes, yes, he is surely a great lord. We will welcome him worthily when he finally finds us. But now, Simmias, would you tell us how things went with that tablet which king Agesilaus had removed from Alcmene’s tomb? Were the Egyptian priests able to decipher it?”

Simmias remembered the story well and gladly told it; he liked to talk about his travels and about the unusual contacts which he’d made in distant lands.

“To tell the truth, I did not see the tablet itself. But a messenger of Agesilaus did indeed arrive in Memphis, in Egypt. I know because I was there at the time, for my studies, together with Plato. We often met a priest there, one Chonouphis. It was to him the Spartan ambassador was directed by the pharaoh. Chonouphis spent three days reading in some ancient books in which all sorts of mysterious systems of writing are explained. Then he wrote to the king, explaining everything in great detail. He told us, too, everything concerning the time period from which the tablet came and the text of the inscription. According to Chonouphis, the style of the script indicates the times of king Proteus, who ruled in Egypt at the time of the Trojan War, or just before it. It is said that Heracles, son of Alcmene, learned this type of script when he was in Egypt and that he brought it back with him to Greece. The text of the tablet was a set of commandments, ordering Greeks to hold games in honor of the Muses, and to live in harmony and peace with each other, competing only in love of wisdom and seeking justice through rational argument rather than not arms. This is what Chonouphis reported and we were thoroughly convinced.”

The commandments which Chonouphis deciphered were lofty, exemplary and edifying. It is therefore not surprising that the philosophers Simmias and Plato enthusiastically endorsed them and accepted the inscription as deciphered. Greeks respected very greatly the wisdom of Egyptian priests and there was a widely held belief that all important skills and all religion originated in the land of the pyramids. Besides, how could one prove to Chonouphis that he was making it all up and that in fact he had not the first clue as to the contents of the tablet? After all, the symbols did appear, at first glance, to be similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs.

But the truth was quite different from the way the Egyptian priest presented it. The script had nothing to do with Egypt. It had a different origin, unknown to anyone at the time, and wrapped in a dark and ancient mystery. The Spartans dug up Alcmene’s tomb after they occupied Thebes and Haliartus, that is to say, not earlier than 382 B.C.; but by then the script on the tablet had been forgotten for eight centuries. It had been lost around the twelfth century B.C. along with the great civilization which had created it.

___________

Commentary:

Today's commentary consists of just one sentence:

What else could one ever expect of a priest?

THE ARCHPRIEST CHONOUPHIS DECIPHERS THE TABLET

Theocritus and his friends chatted about Alcmene’s tomb and waited for Leontiades and his men the leave the house of Simmias the philosopher – it was that very Leontiades who three years earlier had invited the Spartan garrison. Only after he'd gone did the plotters enter the house.

Simmias the philosopher sat upon his bed, lost in somber thought. It was unnecessary to ask: everyone could guess the answer: the pleas have had no result; Amphiteos was going to be executed. At length, after a long silence, Simmias shook off his thoughts. He looked at his guests and sighed:

“By gods, what sort of people were these who’d been here just before you arrived! They are wild beasts, not men! The old saying is right: there is nothing more odd or more disgusting than an old man in power. Even if one experienced no injustice directly himself, it is enough to see the intransigence to come to hate the regime, a regime which breaks the law, feels no responsibility before anyone, and does not even try to hear out rational arguments. Of course, young men often are like this, too, but age adds to it that special ossified inflexibility.”

One could say, in defense of Leontiades, that in his eyes Amphiteos was especially guilty. He was thought to have been the ring-leader of a previous attempt to overthrow the tyrants and their Spartan allies in Cadmea. In fact, the mastermind and animator of that plot had been young Pelopidas, long active in exile in Athens and now leading the seven plotters through the wilds of the Kithairon towards Thebes. But Leontiades did not know any of this.

Meanwhile, Simmias livened up, and, like a true philosopher, set aside oppressive thoughts. He said:

“Well, we must entrust this matter to the gods. Meanwhile, my dear Caphisias, what sort of a stranger was this who’d arrived in your house today?”

Simmias was of course part of the plot, but Caphisias preferred to remain circumspect:

“Who do you mean?”

“Why, Leontiades himself has just told me about it. He’d heard reports that a stranger had been seen at the tomb of Lysis; that he and his retinue had spent the night there; and that he slept on the ground, on a bed of tamarisk and willow. There were also, apparently, traces of some sacrifice of milk, by the remains of the fire. And at dawn he was seen asking people where he might find you, Caphisias, and your brother Epaminondas.”

Caphisias grew alarmed. He had heard no such thing himself; but he had left his house especially early in order to rush to the house of Charon to inquire there how matters stood with the plot, and with the seven coming over from Athens. He began to think aloud:

“Who could it be, that stranger? Surely, a great lord to travel with retinue. Has no one asked him where he was from?”

But Pheidolaos interrupted him impatiently because he was very curious about the story of the funeral tablet and eager to learn more in the matter. He said:

“Yes, yes, he is surely a great lord. We will welcome him worthily when he finally finds us. But now, Simmias, would you tell us how things went with that tablet which king Agesilaus had removed from Alcmene’s tomb? Were the Egyptian priests able to decipher it?”

Simmias remembered the story well and gladly told it; he liked to talk about his travels and about the unusual contacts which he’d made in distant lands.

“To tell the truth, I did not see the tablet itself. But a messenger of Agesilaus did indeed arrive in Memphis, in Egypt. I know because I was there at the time, for my studies, together with Plato. We often met a priest there, one Chonouphis. It was to him the Spartan ambassador was directed by the pharaoh. Chonouphis spent three days reading in some ancient books in which all sorts of mysterious systems of writing are explained. Then he wrote to the king, explaining everything in great detail. He told us, too, everything concerning the time period from which the tablet came and the text of the inscription. According to Chonouphis, the style of the script indicates the times of king Proteus, who ruled in Egypt at the time of the Trojan War, or just before it. It is said that Heracles, son of Alcmene, learned this type of script when he was in Egypt and that he brought it back with him to Greece. The text of the tablet was a set of commandments, ordering Greeks to hold games in honor of the Muses, and to live in harmony and peace with each other, competing only in love of wisdom and seeking justice through rational argument rather than not arms. This is what Chonouphis reported and we were thoroughly convinced.”

The commandments which Chonouphis deciphered were lofty, exemplary and edifying. It is therefore not surprising that the philosophers Simmias and Plato enthusiastically endorsed them and accepted the inscription as deciphered. Greeks respected very greatly the wisdom of Egyptian priests and there was a widely held belief that all important skills and all religion originated in the land of the pyramids. Besides, how could one prove to Chonouphis that he was making it all up and that in fact he had not the first clue as to the contents of the tablet? After all, the symbols did appear, at first glance, to be similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs.

But the truth was quite different from the way the Egyptian priest presented it. The script had nothing to do with Egypt. It had a different origin, unknown to anyone at the time, and wrapped in a dark and ancient mystery. The Spartans dug up Alcmene’s tomb after they occupied Thebes and Haliartus, that is to say, not earlier than 382 B.C.; but by then the script on the tablet had been forgotten for eight centuries. It had been lost around the twelfth century B.C. along with the great civilization which had created it.

___________

Commentary:

Today's commentary consists of just one sentence:

What else could one ever expect of a priest?

25.12.09

In the sala

A day so happy (to get the erudite allusion out of the way right off). I spent it in my sala, which is a steep tiled roof on four massive trunks and stands perched up on top of a small hillock, my garden's highest point. It has views towards distant mountains and a nearly constant easterly breeze. There I lay on my couch, sprawled oriental and decadent fashion, facing west, towards the hills, reading and listening to audio books by turns, dozing off, and staring at the flowering trees and the distant views and listening to the birds. I listened to Le Temps' first chapter some half a dozen times, falling asleep each time, and then waking and falling asleep again, until from the various bits heard and remembered, or sort-of remembered, I got a pretty good impression of what it is about, which is, of course, dozing off. Then I read in Kangxi's autobiography, so cleverly put together from fragments of his edicts by Spence, and was, as always, deeply moved by it: I have known and liked the man for so many years now and, always, the more I learned about him, the more I liked and admired him. Interesting, cultured and decent, men do on occasion arise within our species; odds are, of course, that we will never meet one in the flesh; but the invention of writing allows us to meet them in their words, at least; and when we read them, we know that such men are possible; and therefore that the species is not entirely a waste. There is a warm feeling about the heart. As I lay there on my couch, gradually the day's heat wore off, it leaned towards the evening, the sun set behind the hills without much ado, and darkness began to gather in the air. I lay there absolutely still, waiting for the night. At length the world turned black; a strange bird began to caw; and then I saw a flickering light approaching through the trees: it was my servant coming to collect me and take me home.

24.12.09

Seven Against Thebes (6)

.

THE TOMB OF ALCMENE

The Spartans were still only looking for the tomb of Dirce, but they had not only found, but also dug up the grave of Alcmene, or so Pheidolaos had told the plotters while they stood before the gates of Simmias’ house. But there was no agreement regaring that tomb: whether it was the real tomb of Alcmene, or whether even Alcmene herself had been buried anywhere at all. Thebans themselves told her story as follows:

"Alcmene spent two different periods of her life in our town. She lived here as the wife of Amphitryon, in a house whose ruins still remain near one of the gates. Here she’d been seduced by Zeus, wearing the form of Amphitryon himself, and here she gave birth to her famous son, Heracles. Later, she returned to Thebes following her son's martyrdom and his ascent to Olympus. She died here at very senior age. On the day of her death, Zeus dispatched Hermes who placed in her tomb a heavy rock, raised the dead woman, and carried her off to the far West. There, in the Blissful Isles where there is no snow, no tempest, and where it does not even rain, and only a delicate breeze off the ocean stimulates the residents, Alcmene married Radamanthes; he had once ruled justly over Crete but now rules over the land of the dead. This is how Zeus rewarded the woman whom he had seduced all those years back, and whose son had saved the world from so many terrible trials. Meanwhile, the descendants of Alcmene, the Heraclids, came to her funeral from the distant Peloponnesus which they then ruled. They took her casket upon their shoulders, but as it seemed unusually heavy to them, they opened it and saw only a rock. They set it up in a grove, behind the city, and since that day we worship it as if it were divine."

But many Greeks denied this legend. They claimed that Zeus raised Alcmene to Olympus and that there she resided along with her demi-god son, Heracles.

The residents of Haliartus presented the matter yet differently. This town lies some three hours to the east of Thebes, on the shores of Lake Copais. The Haliartians claimed:

"Alcmene spent her old age in our town. It was here that Radamanthes married her. Exiled from his native Crete he lived among us under the assumed name of Aleus. We have a proof of these ancient connections with the distant island: both here and there the precious bush named styrax blooms. It yields a beautifully scented resin. It was Radamanthes who had brought it here. After many years’ of harmonious life with Alcmene, he reposed here, in a tomb near our city walls."

There was no way to reconcile all these tales; or to decide which one was true. But no one was surprised at it, since yet other localities claimed to possess the tomb of Alcmene. Besides, who would waste his time trying to determine the precise truth content of local tales? The business became important only thanks to certain political and military developments.

As you recall, the conversations of our plotters took place in December 379 B.C. Sixteen years earlier, in the autumn of 396 B.C., Spartans had suffered a painful defeat in a battle against Thebans at the foot of… Haliartus. There they left behind hundreds of their dead. In Sparta investigations began whose purpose was to establish the causes of the defeat: after all, until now it was Spartans who were the greatest military power of all Greece! Pride did not allow Spartans to admit that their defeat may have been brought on by the stupidity of their generals and their foolhardy certainty of their own invincibility. Surely, they argued, the cause of their defeat must lie deeper! It is simply unthinkable that it may have been caused by human hand! Finally, after much research, they have found this:

"Gods and heroes have been displeased by Sparta, because her kings, though they trace their descent from Heracles, failed, over all these centuries, to bring to the fatherland the ashes of the venerable mother of Heracles. This is why they have been dealt a painful defeat precisely at the foot of Haliartus, in the vicinity of Alcmene’s grave."

The Spartans decided to cure their century-old failure as soon as they seized control of the lands of Thebes and Haliartus.

In the year 382 B.C. two mutually-hateful men became the rulers of Thebes: Ismenias, who sided with democrats and Athens; and Leontiades, an oligarch and a conservative. Soon the latter found himself on the defensive. To save himself, he made a secret pact with a Spartan army which passed nearby, on its way north. There was a holiday in Thebes at the time in honor of Demeter; it was called Tesmophoria. Per ancient custom, on that day women ascended the castle hill, Cadmea, in order to perform rites at the goddess’ hilltop shrine while men left the castle so as not to interfere with the rites. Thus, all officers left Cadmea for a day, and even the guards on the walls and at the gates were removed. The Spartans entered the city at noon, when everyone took cover from the merciless midday sun and the streets were practically deserted. They marched calmly right through the middle of the city and seized the castle hill without opposition. As soon as this happened, Leontiades entered the council building at the main city square, where the terrified council members were already assembling. He said:

“The occupation of Cadmea by Spartans should be no cause for concern for anyone. Spartans arrive as friends. They have no hostile intentions towards anyone. Only the warmongers among us need to fear. As for me, I shall act according to the ancient precepts of our holy laws. They allow the polemarchos to arrest without court order any citizen accused of a crime for which the law demands the penalty of death. Rabble-rousing and inciting dangerous wars certainly belong to such crimes. This is why I hereby arrest Ismenias as an enemy of law and order!”

There were many among the councilmen, who – supposedly out of rational calculation, but in fact out of fear – immediately seconded Leontiades. Later, Ismenias was sent to Sparta and there sentenced to death while in Thebes, tyrants and Spartans began to rule. Archias took the place of Ismenias as polemarchos. All opposition was terrorized: who did not manage to flee, was imprisoned, sometimes killed. The largest number of exiles went to Athens.

Once Spartans fortified themselves in Thebes and Haliartus, they dug up Alcmene’s tomb. Its contents revealed that it did date to prehistorical times; the amphorae filled with petrified earth had probably contained ashes of the dead, or perhaps of sacrificial animals; but the true mystery lay in a bronze tablet covered with strange script whose signs looked to some to be Egyptian. This is why the Spartan king Agesilaus sent a copy of it for decipherment to Egypt. The two countries were at that time on good terms and often exchanged embassies.

__________

Commentary:

The book's Polish readers in 1968 would have had no doubt how to interpret this story: Athens -- a democracy, was the US, the exiles -- the Polish government in London, Sparta was Russia and Leontiades and his ilk-- the Polish communist party.

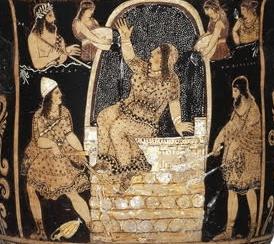

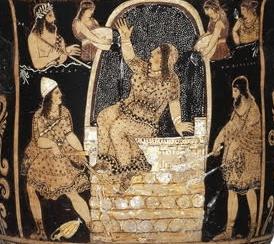

Alcmene on the pyre.

From a crateros of Paestum (c.a. 350-325 B.C.), British Museum

From a crateros of Paestum (c.a. 350-325 B.C.), British Museum

THE TOMB OF ALCMENE

The Spartans were still only looking for the tomb of Dirce, but they had not only found, but also dug up the grave of Alcmene, or so Pheidolaos had told the plotters while they stood before the gates of Simmias’ house. But there was no agreement regaring that tomb: whether it was the real tomb of Alcmene, or whether even Alcmene herself had been buried anywhere at all. Thebans themselves told her story as follows:

"Alcmene spent two different periods of her life in our town. She lived here as the wife of Amphitryon, in a house whose ruins still remain near one of the gates. Here she’d been seduced by Zeus, wearing the form of Amphitryon himself, and here she gave birth to her famous son, Heracles. Later, she returned to Thebes following her son's martyrdom and his ascent to Olympus. She died here at very senior age. On the day of her death, Zeus dispatched Hermes who placed in her tomb a heavy rock, raised the dead woman, and carried her off to the far West. There, in the Blissful Isles where there is no snow, no tempest, and where it does not even rain, and only a delicate breeze off the ocean stimulates the residents, Alcmene married Radamanthes; he had once ruled justly over Crete but now rules over the land of the dead. This is how Zeus rewarded the woman whom he had seduced all those years back, and whose son had saved the world from so many terrible trials. Meanwhile, the descendants of Alcmene, the Heraclids, came to her funeral from the distant Peloponnesus which they then ruled. They took her casket upon their shoulders, but as it seemed unusually heavy to them, they opened it and saw only a rock. They set it up in a grove, behind the city, and since that day we worship it as if it were divine."

But many Greeks denied this legend. They claimed that Zeus raised Alcmene to Olympus and that there she resided along with her demi-god son, Heracles.

The residents of Haliartus presented the matter yet differently. This town lies some three hours to the east of Thebes, on the shores of Lake Copais. The Haliartians claimed:

"Alcmene spent her old age in our town. It was here that Radamanthes married her. Exiled from his native Crete he lived among us under the assumed name of Aleus. We have a proof of these ancient connections with the distant island: both here and there the precious bush named styrax blooms. It yields a beautifully scented resin. It was Radamanthes who had brought it here. After many years’ of harmonious life with Alcmene, he reposed here, in a tomb near our city walls."

There was no way to reconcile all these tales; or to decide which one was true. But no one was surprised at it, since yet other localities claimed to possess the tomb of Alcmene. Besides, who would waste his time trying to determine the precise truth content of local tales? The business became important only thanks to certain political and military developments.

As you recall, the conversations of our plotters took place in December 379 B.C. Sixteen years earlier, in the autumn of 396 B.C., Spartans had suffered a painful defeat in a battle against Thebans at the foot of… Haliartus. There they left behind hundreds of their dead. In Sparta investigations began whose purpose was to establish the causes of the defeat: after all, until now it was Spartans who were the greatest military power of all Greece! Pride did not allow Spartans to admit that their defeat may have been brought on by the stupidity of their generals and their foolhardy certainty of their own invincibility. Surely, they argued, the cause of their defeat must lie deeper! It is simply unthinkable that it may have been caused by human hand! Finally, after much research, they have found this:

"Gods and heroes have been displeased by Sparta, because her kings, though they trace their descent from Heracles, failed, over all these centuries, to bring to the fatherland the ashes of the venerable mother of Heracles. This is why they have been dealt a painful defeat precisely at the foot of Haliartus, in the vicinity of Alcmene’s grave."

The Spartans decided to cure their century-old failure as soon as they seized control of the lands of Thebes and Haliartus.

In the year 382 B.C. two mutually-hateful men became the rulers of Thebes: Ismenias, who sided with democrats and Athens; and Leontiades, an oligarch and a conservative. Soon the latter found himself on the defensive. To save himself, he made a secret pact with a Spartan army which passed nearby, on its way north. There was a holiday in Thebes at the time in honor of Demeter; it was called Tesmophoria. Per ancient custom, on that day women ascended the castle hill, Cadmea, in order to perform rites at the goddess’ hilltop shrine while men left the castle so as not to interfere with the rites. Thus, all officers left Cadmea for a day, and even the guards on the walls and at the gates were removed. The Spartans entered the city at noon, when everyone took cover from the merciless midday sun and the streets were practically deserted. They marched calmly right through the middle of the city and seized the castle hill without opposition. As soon as this happened, Leontiades entered the council building at the main city square, where the terrified council members were already assembling. He said:

“The occupation of Cadmea by Spartans should be no cause for concern for anyone. Spartans arrive as friends. They have no hostile intentions towards anyone. Only the warmongers among us need to fear. As for me, I shall act according to the ancient precepts of our holy laws. They allow the polemarchos to arrest without court order any citizen accused of a crime for which the law demands the penalty of death. Rabble-rousing and inciting dangerous wars certainly belong to such crimes. This is why I hereby arrest Ismenias as an enemy of law and order!”

There were many among the councilmen, who – supposedly out of rational calculation, but in fact out of fear – immediately seconded Leontiades. Later, Ismenias was sent to Sparta and there sentenced to death while in Thebes, tyrants and Spartans began to rule. Archias took the place of Ismenias as polemarchos. All opposition was terrorized: who did not manage to flee, was imprisoned, sometimes killed. The largest number of exiles went to Athens.

Once Spartans fortified themselves in Thebes and Haliartus, they dug up Alcmene’s tomb. Its contents revealed that it did date to prehistorical times; the amphorae filled with petrified earth had probably contained ashes of the dead, or perhaps of sacrificial animals; but the true mystery lay in a bronze tablet covered with strange script whose signs looked to some to be Egyptian. This is why the Spartan king Agesilaus sent a copy of it for decipherment to Egypt. The two countries were at that time on good terms and often exchanged embassies.

__________

Commentary:

The book's Polish readers in 1968 would have had no doubt how to interpret this story: Athens -- a democracy, was the US, the exiles -- the Polish government in London, Sparta was Russia and Leontiades and his ilk-- the Polish communist party.

23.12.09

A vignette written to celebrate my commencement of reading Le Temps Perdu

At daybreak I woke up remembering the rain.

It had woken me in the middle of the night: the patter on the roof, the murmur in the bamboo outside. Delighted and confused -- was I dreaming? -- I got up and walked out naked onto the terrace. It does not rain here in December. Ever. When God made the world, he had declared that there should be no rain in these parts until May. Yet, there it was, the rain: the surface of my pond, black, oily and glistening in the dim light of a single yellow lantern among the bamboos on the other side sprang growing circles where individual drops of rain fell upon it: here, there, here.

At daybreak I woke up remembering the rain. I walked out onto the terrace again, trying to ascertain whether I had dreamt it: there was dew on the trees, the ground was wet. Did it rain last night, or did I dream it?

I looked around. The sky was overcast and the air was humid. It's never humid this time of the year. There are not supposed to be any clouds in the sky. Have I woken up in a different part of the world from that in which I had gone to sleep? Was I dreaming still? I felt displaced. The experience was confusing but it was pleasant to be confused: I had been tired with my old reality, I had grown desperate thinking that it would never change. An unexpected tectonic shift in it would have been welcome; falling into a time-space anomaly like this would have been an answer to my prayers.

I search for clues to the mystery of where it is I had woken, I began to wonder through my garden, looking at the flowers and the trees, until I came upon my neighbor's hut. He was on his porch, making coffee.

Theo, I asked him, did it, or did it not rain last night? Nope, he said definitively.

By the pool I met Annette. Annette, I said, did it rain last night? Most certainly not, she said and dove in the pool.

Then, suddenly, I remembered something. Doubling back by Theo's house, I asked him: Theo, do you think it is possible that there might have been a dog drowning in my pond last night?

Wouldn't know anything about that, said Theo. But would you like some coffee?

I walked back home slowly.

There most definitely had been a drowning dog in my pond last night. I remembered it now. Her yelping disturbed my reading several times, until at last, taking my torch in hand, I headed out to see what the matter was. After some searching I discovered her, her eyes squinting in the beam of my flashlight, in the bushes on the other side of my pond. She lay exhausted half-way on the ground and half-way in the water. She must have come down to drink, slipped and fallen in; but as the bank is very steep and slippery here, she couldn't scramble out. She struggled and struggled and at last collapsed breathless, slowly slipping back into the water where she was going to drown. And now she lay there, yelping, resigned to death by water.

Laying my torch on the ground, I stripped, wrapped my arms in my jeans in case she should scratch or bite, stepped in the pond up to my waist, and lifted her up. She offered no resistance. She was as motionless as dead. I carried her to the garden gate and gently put her outside, on the road, in the moonlight shining through an opening in the clouds. She looked miserable, wet and trembling, and had the world's stupidest expression on her snout. Have you ever seen an embarrassed dog? As I locked the gate behind her, she looked at me, confused.

Yes, I now remembered that. It had happened last night. And then I went to sleep. And then I woke in the middle of the night: the patter of the rain on the roof had woken me, and its murmur in the bamboo. And then I went to sleep again. And then I woke uncertain whether any of that had happened or not.

It had woken me in the middle of the night: the patter on the roof, the murmur in the bamboo outside. Delighted and confused -- was I dreaming? -- I got up and walked out naked onto the terrace. It does not rain here in December. Ever. When God made the world, he had declared that there should be no rain in these parts until May. Yet, there it was, the rain: the surface of my pond, black, oily and glistening in the dim light of a single yellow lantern among the bamboos on the other side sprang growing circles where individual drops of rain fell upon it: here, there, here.

At daybreak I woke up remembering the rain. I walked out onto the terrace again, trying to ascertain whether I had dreamt it: there was dew on the trees, the ground was wet. Did it rain last night, or did I dream it?

I looked around. The sky was overcast and the air was humid. It's never humid this time of the year. There are not supposed to be any clouds in the sky. Have I woken up in a different part of the world from that in which I had gone to sleep? Was I dreaming still? I felt displaced. The experience was confusing but it was pleasant to be confused: I had been tired with my old reality, I had grown desperate thinking that it would never change. An unexpected tectonic shift in it would have been welcome; falling into a time-space anomaly like this would have been an answer to my prayers.

I search for clues to the mystery of where it is I had woken, I began to wonder through my garden, looking at the flowers and the trees, until I came upon my neighbor's hut. He was on his porch, making coffee.

Theo, I asked him, did it, or did it not rain last night? Nope, he said definitively.

By the pool I met Annette. Annette, I said, did it rain last night? Most certainly not, she said and dove in the pool.

Then, suddenly, I remembered something. Doubling back by Theo's house, I asked him: Theo, do you think it is possible that there might have been a dog drowning in my pond last night?

Wouldn't know anything about that, said Theo. But would you like some coffee?

I walked back home slowly.

There most definitely had been a drowning dog in my pond last night. I remembered it now. Her yelping disturbed my reading several times, until at last, taking my torch in hand, I headed out to see what the matter was. After some searching I discovered her, her eyes squinting in the beam of my flashlight, in the bushes on the other side of my pond. She lay exhausted half-way on the ground and half-way in the water. She must have come down to drink, slipped and fallen in; but as the bank is very steep and slippery here, she couldn't scramble out. She struggled and struggled and at last collapsed breathless, slowly slipping back into the water where she was going to drown. And now she lay there, yelping, resigned to death by water.

Laying my torch on the ground, I stripped, wrapped my arms in my jeans in case she should scratch or bite, stepped in the pond up to my waist, and lifted her up. She offered no resistance. She was as motionless as dead. I carried her to the garden gate and gently put her outside, on the road, in the moonlight shining through an opening in the clouds. She looked miserable, wet and trembling, and had the world's stupidest expression on her snout. Have you ever seen an embarrassed dog? As I locked the gate behind her, she looked at me, confused.